Legal protections around passkeys

One lesser-discussed aspects of passwords vs passkeys is the legal protections that apply, and how they can differ.

First, a disclaimer

Important: we are not lawyers, and are not providing legal advice. Consider this to be a starting point for your own research.

Note that this is a US-centric topic, specially around the Fourth Amendment. Legal implications will vary widely by country, phase of the moon, or whether a judge was hungry when ruling. Proceed with care.

With that out of the way...

The Fourth Amendment of the US Constitution reads as follows1:

The right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated, and no Warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause, supported by Oath or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched, and the persons or things to be seized.

To date, information in your mind has generally been protected by the Fourth Amendment. There are wide-reaching implications to that; in the computer security space, that notably includes passwords and PINs.

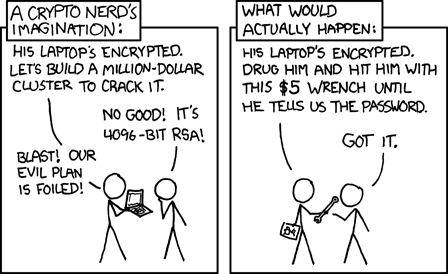

Which is to say, you generally can not be legally compelled to divulge a password.

That doesn't mean there aren't practical risks, but to date, the legal system has generally protected passwords.

Password managers

The security model of password managers varies widely, with some focused on the highest security levels and others opting for more convenience. This can have implications on legal protections for the data they manage.

To (over) simplify, it's best to test what happens on an unlocked device. Does autofill work without re-authenticating? Hand your unlocked device to a trusted friend and see if they can sign in to a website. If they can, so could law enforcement (or anyone else that manages to take your device).

With very rare exception, password managers are a huge security improvement for interacting with password-based sites, since they make unique and complex passwords practical.

Passkeys are different

Unlike passwords, which are something you know, passkeys are something you have. On-device, there are additional protections keeping them locked and secure until they're ready to use (typically biometrics or a password/PIN).

While there's no practical way to reveal the contents of a passkey to someone, the biometric protections have typically not been covered by the Fourth Amendment. Simply put, there have been cases where suspects have been compelled to unlock their biometrics-protected device by the police, and that has not been considered "unreasonable" by the courts.

This means that passkey-only authentication can, in some circumstances, have less legal protection than passwords - even though they're far more secure against breaches and phishing than passwords. This risk is not specific to passkeys, but they tend to be impacted more than passwords directly (a biometrics-protected password manager would be equally affected).

Further note: in this case, the distinction between passkeys and WebAuthn matters. An external hardware security key (which is a WebAuthn authenticator) could have different legal protections than a passkey.

What this means

Here at SnapAuth, we believe in making informed security decisions. As such, we believe it's important to call attention to these subtleties. They may or may not matter for you, but this could be critical in certain circumstances.

For most people, this has no day-to-day impact. It's typically relevant only during interactions with law enforcement.

As a website or app operator

You should be aware of this, and adjust your threat model accordingly.

If you're running a forum, web store, or something else that's typically lower-stakes, this may not matter at all. Conversely, if you're running a financial service or end-to-end-encrypted communication tool, this may make a great deal of difference!

Passkeys are usually an excellent option that greatly increases both security and convenience for your users.

If you want the implied legal protections afforded to knowledge factors, going passkey-only isn't appropriate. Perhaps they're better suited as only a second factor in a more comprehensive authentication model.

Or you may want to use WebAuthn with only external hardware tokens, disabling passkeys. In extreme circumstances, it may even be appropriate to allow users to register distress passkeys or passwords that have distinct results when used.

As an end-user

It's good security hygiene to ensure that all of your devices get "hard-locked" any time they're out of your possession or you're in an encounter with law enforcement. This means disabling biometric auth until you re-enter your PIN or password.

In particular, you should do this during a traffic stop, at airport security, border control2, etc. If you're going near a protest, maybe leave your phone powered off or at home. This is true whether you've migrated all of your logins to passkeys, or have never used one in your life.

For nearly all devices, restarting will require a password or PIN before the device can be unlocked again.

On iOS, you can also press and hold the sleep/wake and a volume button for about two seconds. You should feel some haptic feedback. This can be done covertly without removing the device from your pocket, so is a great shortcut to remember.

On Android, the same button combination should work, but you may need to then tap an on-screen "Lockdown" icon.

Check with your device or operating system for specific details.

Want to discuss?

Please contact us - we're happy to chat about your requirements and technical trade-offs. No sales pitch. We want the web to be more secure, period.

For most situations, we can help you enhance overall security as well as user convenience. If you're trying to guard against state-sponsored attacks, you may be better off self-hosting a WebAuthn backend, and we're happy to tell you that.

congress.gov; see also annotated discussion at congress.gov and uscourts.gov discussion. ↩

Border crossings in particular tend to have lower legal protections, and laws of multiple countries are involved. Even if you can't be forced to reveal a password, you could still be refused entry or held indefinitely for not cooperating. If you think this is relevant to you, talk to your lawyer. ↩

SnapAuth

SnapAuth